Walking a New Beat With Those We Serve

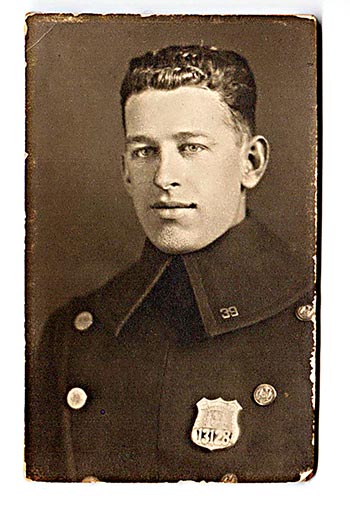

Officer Edward Phelan of the old 72nd precinct in Brooklyn waked the beat for 24 years with his friends and neighbors.

My father was a New York City cop in the old 72nd precinct in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn during the 1940s.

His job included guarding a gigantic hole in the ground that would later become the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, being a crossing guard and generally keeping an eye on the neighborhood—one of the poorest and most ethnically diverse communities in New York City.

Dad felt that his back was not only covered by his fellow officers, but also by the residents of Red Hook. It was clear that he earned their trust and protection by the way he policed the neighborhood, which he knew well because he was recruited for the job from one of its street corners. He spent most of the day in conversations with residents as he walked the beat, no matter the weather or the season. He made sure teenagers were more often delivered home for family adjudication instead of to the precinct. He was a meat-and-potato guy, but learned to appreciate Italian and Chinese cuisine with neighborhood families on dinner break. And on nights when the weather turned particularly bad, Dad was always welcomed by Joe Fung in the back room of his laundry shop.

There is a note I discovered among Dad’s things I will always cherish—a letter addressed to him at home in Brooklyn from a young elementary school student. After leaving his street crossing post, the boy wrote to him at home and said he missed my father on the crossing. He thanked him for his advice and presence, and wanted Dad to know that he was doing much better in school.

Lesson 1: Today

The manner in which these New York City cops—from a seemingly long gone era—worked with the residents might not be deemed appropriate today, especially given the recent events in Ferguson, Baltimore and Staten Island. But this type of relationship is exactly what is needed today.

In predominantly poor neighborhoods in cities across the US today, it is clear that officers deliver their brand of policing “to” the population and not “with” the population—holding great disregard for their rights and providing zero notion of community policing. It seems they believe residents are to be managed—told, supervised and even punished sometimes—on the spot or in the police van. Only in the better neighborhoods with reduced racism and classism are residents treated differently. Police departments—like many other institutions in our society —severely limit their effectiveness by concentrating on their service “to” the population with little understanding of how it could be delivered more effectively, efficiently and simply “with” them.

Lesson 2: Lasallian Family

The Lasallian family of which I am a part is made up of over 80,000 Christian Brothers (like myself), men and women teachers, administrators, counselors and staff in nearly 1,000 colleges, high schools, middle schools, and child care institutions around the globe. From where I stand in a world filled with caring educators and counselors, it is clear to me that we must also bring the “to” and the “with” into balance. For almost 300 years since its founding in France, this family of Lasallian educators was almost entirely made up of De La Salle Christian Brothers, and their mission was human and Christian education “to” the poor—not “with” the poor.

Since the 1950s and Vatican II, these Brothers have shared their mission with so many lay women and men that the Brothers today only account for less than 3% of the Lasallian family. Yet the number of students reached four times what it was when Vatican II opened.

Lesson 3: One Lasallian Changes the Beat

Recently, this family of Lasallian educators added “with” to their mission statement that was once a service “to the poor.” In February of 2014, the International Symposium of Young Lasallians—a subset of the Lasallian family—met in Rome to discuss their mission in the world today. Sarah Laitinen, a teacher from Rhode Island, shared a part of her 8-years of experience at San Miguel School in Providence, a middle school for over 80 boys in the surrounding neighborhood that is primarily poor.

“We at San Miguel are always asking parents what they think is needed for their children,” says Latinen. “They are invited to tutor or coach, or just spend quality time with our boys.” She described the San Miguel mission as serving “with” the families instead of “to” the families, and repeated Pope Francis’ call for authentic collaboration with the poor.

Latinen’s words were loud and clear—in short order, a majority of those present supported her idea and added their own stories. In a remarkable show of support for Latinen’s idea, the General Chapter of De La Salle Christian Brothers from every part of the world not only agreed with the language and concept of service “with” the poor but made it clear that the whole family works “with” one another in delivering that service.

One proposition stated, “The Chapter reaffirms its global commitment to association for educational service with the poor…” Their logic was that of Pope Francis’ invitation “to be an instrument of God for the liberation and promotion of the poor, and for enabling them to be fully a part of society.” (EG 187).

Final Lesson: Working “With” Not “To”

In the 2015 revised rule of the De La Salle Christian Brothers, they addressed how the Lasallian mission is expanded in secularized and multicultural contexts as such: “The Brothers strive to enter into a respectful dialogue with the persons they are called to serve. This attitude presupposes openness and a willingness to listen, to learn, to witness Gospel values, and, as far as possible, to announce the Word of God.” (14.1)

On a personal level, years before these international developments I instinctively decided to help a group of Bronx moms realize their dream of leadership, finance and community development classes for their neighbors. After a few short months–and lots of meetings and credit checks from Manhattan College–our courses were offered in the basement of our St. Augustine School. With extraordinary growth and a newly expanded home on 150th Street this creative program became a campus of the School of New Resources of the College of New Rochelle.

It had only one degree: a BA in the Liberal Arts. Throughout each semester students gathered support for their ideas, generated course content, and wrote the course descriptions that would all become the curriculum for the next semester. All course descriptions were voted on by the student body to identify which ones should go into the course catalog. Creativity and excitement prevailed as the students realized that they were the principal stakeholders in the college, and the school thrived and grew.

Working “with” the poor shines in the Christian Brothers’ volunteer program. Young women and men Lasallian Volunteers live in intentional communities with De La Salle Christian Brothers for a year or two of service with children and adults of some of the poorest neighborhoods in our country—in cities much like Ferguson, Staten Island and Baltimore. The community they experience, in living with each other and with their neighbors, changes them for life. They have an orientation session at the beginning of their service year that focuses on the topic of investing in local communities. They learn to be sensitive and aware of the real needs of people and families in their neighborhood.

Lasallian Volunteer Steven Patzke and I share our intentional community with other men, women and De La Salle Christian Brothers in Bronx, New York. Patzke is quick to point out that other charisms in the church are pointed in the same direction.

“I was not long at Loyola Chicago when I began hearing about a language shift in the Jesuit value from ‘men and women for others’ to ‘men and women for and with others,’” Patzke says. “It showed the need to meet people where they were rather than where we think they should be.”

On the Street, Miracles Can Happen

It is never easy to bring about institutional change—especially in the decaying neighborhoods of our cities. With people like Sarah Latinen, small armies like the Lasallian family and similar groups in other traditions, hope emerges. When it does, it usually can be traced to a single, thoughtful, sensitive leader.

The New York Times captured New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s effort to reform the police department as “a ‘pioneering’ step in police reform, the city is expected to debut a new neighborhood-based policing model, in which patrol officers would be given about one-third of their day away from radio calls to develop closer relationships with residents of their precincts.”

In his day, my dad was just such an officer, spending more time with those he served than with the data and equipment that came with the job. If he were here today, he would be delighted at this news from the mayor, and I would expect he would see the example of his life carried on to his son even in a different capacity as a De La Salle Christian Brother–ministering always with people and not to people. What a concept!

Brother Ed Phelan, FSC, 75, is Auxiliary Provincial of the De La Salle Christian Brothers for the District of Eastern North America. He has lived in intentional communities in the South Bronx for many years and has worked with families and children in educational and community organizing projects.

Hi Ed Hope you remember me from our time together at St Augustine. I’m glad to see you’re still fighting the good fight. I remember meeting your dad one night with the former commissioner I taught in the Wayne NJ school system for 30 yrs until retirement. I spent the next 7 yrs as an elected official in my town. The 1st Democrat in a 15 yrs. A long battle with cancer ended that but I am now cancer free 5 yrs ! Happy New Year

Harold